Jack Skingley

This story and photos are shared by the Trust with kind permission from his daughter, Jackie

Jack was a wonderful husband to Marjorie and a loving father to their two young children, Jacqueline and Ross. From an early age, Jack’s desire to serve and make a difference was obvious to all who knew him – it began when he threw himself enthusiastically into the Scout movement and the same drive led him to enlist in the Royal Air Force in 1941.

Jack was born in Watford, Hertfordshire on 7 July 1916, the only child of Winnifred and Sidney Skingley. Sidney served in the Mounted Military Police during WW1 and later with Sussex Constabulary until his early death in 1934 when Jack was 18 years old.

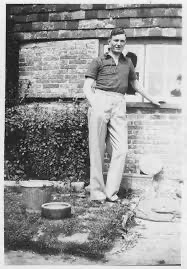

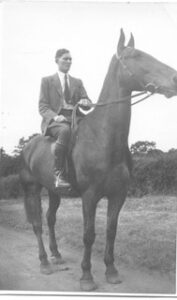

As a boy, Jack frequently visited his relatives in Balcombe, Sussex, especially Woodward’s Farm which belonged to his Aunt Kitty and Uncle Fred. Jack was a proficient horseman, like his father, and loved the countryside.

L-R Jack at Woodward's Farm and seated on his horse

As a teenager he was presented with the King’s Scout Award – one of many proud moments for the family.

Jack being presented with the King's Scout Award

In 1934, Jack served two years with 1st Battalion, The Royal Sussex Regiment and later followed in his father’s footsteps when he joined the Police Force in Reigate, Surrey. Jack’s personnel record at the time described him as 5’11” tall, with a fresh complexion, brown hair and grey eyes.

Jack in police uniform

Whilst on the beat in Reigate, Jack noticed an attractive young lady called Marjorie Henderson. Unable to get Marjorie out of his mind, Jack summoned up the courage and wrote a handwritten note which he posted through her letterbox – it included an invitation to go dancing. Luckily for Jack, Marjorie accepted! The pair soon became inseparable and were married on 18 November 1940 at St Mark’s Church, Reigate followed by a reception at Reigate Hill Hotel.

Jack and Marjorie on their wedding day

It was not a peaceful period for the newlyweds, the Battle of Britain had just ended and the Blitz was destroying countless lives across the country. The war was inevitably at the forefront of Jack’s mind and he became determined to enlist in the RAF, not an easy decision but one he discussed at length with Marjorie. Being in a reserved occupation, Jack sought permission from his police Chief Constable before he signed up.

In April 1941, Jack enlisted in the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve (RAFVR) and attended No 10 Initial Training Wing at Scarborough in August the same year. Jack and Marjorie’s daughter, Jacqueline (Jackie), was born that November.

Jack and Marjorie pictured with their daughter, Jackie in June 1943.

The following April, Jack headed to Canada for officer training in Caron, Trenton, Fingal, Chatham, and New Brunswick. Jack received his Commission as Flying Officer in November 1942.

Jack, standing top right, whilst on officer training in Canada. Other men unknown.

Following operational training at RAF Benson in Oxfordshire, Jack was posted to 7 Squadron, RAF Oakington on 28 June 1943. He flew six missions in Lancaster bombers across Germany: Nuremburg, Milan, Hannover, Munich, Kassel and Stuttgart. Jack’s role was that of Bomb Aimer which required him to take control of the aircraft when it was on its bombing run. He would lie flat in the nose of the aircraft, directing the pilot until the bombs were released and the bombing photograph was taken - the photograph providing proof of a successful mission. The bomb aimer could also act as reserve pilot if circumstances required it.

Posted in October 1943 to 207 Squadron, RAF Spilsby in Lincolnshire, Jack became part of the Benton Crew and made a lifelong friend in Eric Rimmington (Engineer).

An extract from Eric Rimmington’s letter to Jack’s daughter, Jackie, dated 15 August 2005:

When I do look back into the past and think of the men I flew with, I am the last surviving member, I think of your father and remember him as being a very thoughtful man and his family would always come into the conversation. Prior to take-off when we were on Ops, we had to be out at the aircraft an hour before take-off time, this was to check everything, we then had to wait around for what seemed ages, that is when I enjoyed talking to your father, not all about the target, but about life in general, we always steered clear of the task ahead which was good, but it was with these conversations that I got to know Jack very well.

I was posted to 207 Squadron to start Operational flying when they were at Hangar that was in June ’43. In October the whole squadron moved to Spilsby, it was shortly after this that our Bomb Aimer was tragically killed when he fell off the Aircrew wagon, it will be then that Jack came into our crew. At the latter part of December, our crew were posted to 97 PFF* Squadron who were then at Bourn, Cambridgeshire. After a week or so getting to know the techniques of PFF flying, we did our first operation with 97 on 14 January ’44 to Brunswick. Jack did a further six trips with us, the last one was on the night of 30/31 March when we went to Nuremburg when we lost 96 Lancasters over Germany with a further 15 crashing over this side due to damage from flak and fighters.

* PFF: Pathfinder Force were target-marking squadrons in RAF Bomber Command during WWII. They located and marked targets with flares, at which a main bomber force could aim, increasing the accuracy of their bombing.

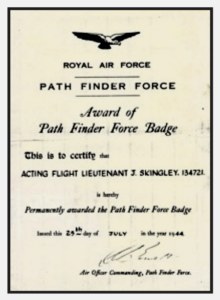

Jack's Pathfinder Force Certificate

Jack completed one mission to Modane, France and five missions to Berlin with the Benton crew of 207 Squadron. On 2 December 1943 their Lancaster was hit by flak on the way back from Berlin, resulting in large holes in the fuselage, nose, both turrets and tail plane. The intercom, oxygen economiser, and rams to the turrets and bomb doors were also damaged. Incredibly the aircraft managed to limp home.

On 19 December 1943, Jack transferred with the Benton crew to 97 Pathfinder Squadron (motto Achieve Your Aim) and was granted leave over Christmas. He travelled to his widowed mother-in-law’s house where he was reunited with Marjorie and their daughter, Jackie. Years later Jackie learnt that when her father was home before his last sorties he made a point of saying goodbye to every member of the family, and even kissed one he didn’t particularly like! Marjorie felt certain that Jack had a premonition of his death, hinted at in a letter from Jack to his Uncle Walter in January 1944:

Christmas was kept at Holmesdale Road with my mother and self present and Jackie had the time of her life. I took a walk up the hill and cut our Christmas tree from a mass of young forest in good tradition, having a drink on the fruits of my labour, and on the Eve decorated it with all kinds of coloured wool and with cotton wool as snow - one gets an awful lot of pleasure from the kiddies enjoyment of these things and with our second infant almost with us I look forward to our first Christmas of Peace with our own home. ….There seems to be a big danger of the Skingleys fading into extinction, a horrible thought but very real so I am hoping and praying for a boy this time…

Jack and Marjorie’s son, Ross, was born a month later.

Jack flew with the Benton Crew until the end of March. During this period he completed another six missions to Brunswick, Berlin, Stuttgart, Augsburg, Frankfurt and Nuremberg.

In April 1944, 97 Squadron moved to RAF Coningsby in Lincolnshire and Jack transferred to the Edwards crew a few days later, having previous flown with them in January to Berlin. Jack completed a further 15 missions including Paris, Munich, Schweinfurt, Oslo, Toulouse, Mailly-Le-Camp, Amiens, Brunswick, Eindhoven, St Valery-en-Caux, Maisy, Clermont-Ferrand, St Pierre-du-Mont, Châttellerault, Argentan, Gelsenkirchen and Thivergny.

The Mailly-Le-Camp mission was particularly difficult. Group Captain Leonard Cheshire, Marker Leader for bombing on this occasion, gave the order for the Main Force to go in and bomb after markers were dropped. The Controller did not hear the order due to a faulty VHF radio. German night fighters took advantage of the circling bombers lit up in bright moonlight and wreaked havoc, causing heavy casualties. Finally, the order came from the Deputy Controller and fierce bombing began. Smoke obscured the markers. A call to cease fire ensued but not all the bombers complied, making re-marking more hazardous. Jack, in his role as Bomb Aimer, was called to go in with the Edwards crew from the 97 Pathfinder Squadron to mark the western edge of fires that were burning, with a slight undershoot. Jack succeeded in placing his ten flares in exactly the precise spot, allowing the second wave of bombing to commence. Jack was congratulated by Group Captain Cheshire and received an ‘excellent’ from the Controller.

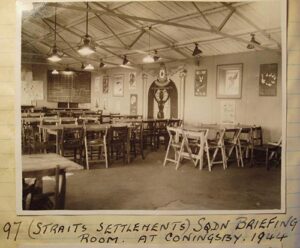

97 Squadron RAF Coninsby Briefing Room 1944 (Credit: 97 Squadron Association)

On the night of the 20 July 1944, Jack with his crew in Lancaster PA979R left RAF Coningsby at 2319 hours headed for Belgium – the objective to bomb railway yards. PA979R was accompanied by a further 14 squadron aircraft. By this point in the war, 97 Squadron had undertaken over 3,000 sorties and lost more than a 100 aircraft. It was Jack’s 39th mission and would tragically be his last.

Following take-off, nothing more was heard from PA979R and the Operational Log records ‘aircraft lost in action’. The eight-man crew made the ultimate sacrifice for our freedom and their names are inscribed on the British Normandy Memorial. The final resting place of the aircraft and her crew has never been discovered.

Jack Skingley named on the British Normandy Memorial

Marjorie knew the exact second Jack was killed. She was asleep in the cellar of the house in Reigate alongside her two young children and her mother. Suddenly Marjorie woke up and said to her mother, “Jack has just died”.

First came the telegram - reported missing as the result of air operations - then confirmation that he would never return.

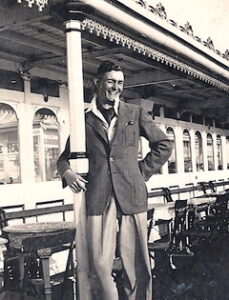

Determined to keep his memory alive, Marjorie would often talk about Jack with her children, who were incredibly young when their father died. Jack was a wonderful dancer and had a great sense of humour, like his mother. He was a very ‘dapper’ dresser as can be seen in this picture of him in Brighton, Sussex.

Jack on a trip to Brighton

As a couple, he and Marjorie had a lot of fun despite the war and Jack cherished his role as father to Jackie and Ross. Marjorie and Jack were married for just three years and eight months but they had made every moment count.

The January 1946 edition of the London Gazette confirmed Flt Lt Jack Skingley was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for "the utmost fortitude, courage and devotion to duty", with effect 20 July 1944 (posthumous).

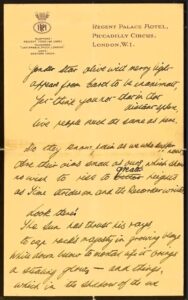

The following poem was written by Jack and has been donated by the Skingley family to the RAF Pathfinders Archive. The poem is undated but was written on Regent Palace Hotel notepaper where RAF personnel often stayed while on leave in London. It is possible Jack wrote this after losing his best friend, Squadron Leader Eric Woods, DFC and bar, who was killed on 16 December 1943 off the Greek coast flying his Spitfire. Jack and Eric had served together in the Reigate Police Force and Eric was godfather to Jack’s daughter.

The first page of Jack's poem

OUR HEROES

Yonder star alive with a merry light

appears from Earth to be inanimate,

Yet think you not that in that distant sphere,

live people much the same as here?

Do they know pain as we who suffer now,

Are their aims small as ours, which show

no wish to rise to greater heights

as Time strides on and the Recorder writes?

Look there!

The sun has thrust his rays,

to cap rock’s majesty in growing blaze

While down below to mortal life it brings

a stealing glow – and things,

which in the shadow of the eve

gained magnitude, now die to leave

the thought that yester took but little joy from Life

When man can face the growing strife

now prevalent in this troubled world

by honouring a Flag unfurl’d.

Those soldiers who paraded in the Past

Fought War and left Death’s aftermath,

Their ghosts now stand with Youth to guide their feet,

To make it easier when the drummers beat

and “Last Post” sends its poignant prayer

“Oh! God, receive these Heroes in Thy Care.”

Oh God, I pray that it may be

that when our nation’s history

Stands recorded in Truth’s clear light

no blot appears to mar the sight

Of noble sacrifice by those who tried,

with Hope and Loyalty allied,

to stop a Monster’s greed for power

and put an end to War for ever.

Their loyalty unites in tempered band

True friendship proffered with unstinting hand.

If theirs to die the clasp is strong

The greater sacrifice, the better bond.

In vision clear as to their destiny

These men will fight for Right unceasingly,

So charge your cups and stand in prideful pose

To drink a toast to Victory and to those

who counted not the price for Conquest paid,

Unfaltered in their purpose firmly made,

To rid the World of horror and of vice,

They give their lives, what Greater Sacrifice!

I give you ‘Our Heroes’.

Reflecting on the poem in 2005, Jack’s friend and RAF colleague, Eric Rimmington, wrote, “I think that the poem, reading it slowly to get the full meaning, shows what a wonderful mind Jack had - a true Englishman.” Jackie corresponded with Eric for many years and finally met him at a RAF Bourn reunion in 2014 – it was a very emotional day. Eric died in 2016 aged 95 – he never forgot Jack.

Family reflections

ROSS SKINGLEY: Jack’s son, Ross was born in 1944 and died in 2023. Ross was a little over five months old when Jack was killed, the father he never knew and hero-worshipped.

As a small boy Ross developed a passion for making model aircraft and from this came his love of flying. He once said he’d followed in his dad’s footsteps. Ross joined the Royal Army Service Corps as a soldier. He desperately wanted to fly and after training was selected to be an Air Dispatcher flying with the RAF in transport aircraft. He served in Africa and Aden and earned his wings on 20 operational flying sorties. Ross transferred to the Army Air Corps (AAC) and trained as Navigator and Second safety pilot and was awarded his Observer Wing, the same badge Jack wore on his uniform.

Ross also served at Oakington and flew his own aircraft, an Auster, from Bourn. Jack was promoted to Flight Lieutenant and Ross rose through the ranks to Captain. After retirement Ross marched every year past the Cenotaph leading 656 Squadron AAC, wearing his military medals and those of his father. Jack would have been very proud of his son.

JACKIE SKINGLEY: towards the end of October 1953, my mother escorted my brother and me to the RAF Memorial at Runnymede in Surrey. On 17 October that year, HM The Queen had officially opened the memorial, which commemorates more than 20,000 service men and women of the Commonwealth Air Forces who died during operations from bases in the United Kingdom and North and Western Europe and who have no known grave.

Just 11 years old at the time, I remember a stone building with arches and the names of dead airmen carved on panels. I think my mother had an invitation because she knew where to find our father’s inscription. It was the first time I realised how many men had lost their lives and had never been found, name after name until we came to panel 203 and S alphabetically to find Flt Lt Jack Skingley. How I wished I’d known him, now only a name amongst others.

I had a few vague memories of him: holding me up to touch the ceiling when he came home on Christmas leave in 1943; at the family farm in Bedford, where my Granny lived, a few months after my brother was born; daddy on a horse, so high up. I was two years and seven months old when he was killed. I’m proud to be called Jackie after him.

Runnymede Memorial (Credit: Commonwealth War Graves Commission)

In the early 2000s, I began researching my family tree having received the gift of a personal computer from my son. Keen to find out more about my father, I located a website for 97 Squadron RAF. The webmaster at the time was Des Evans and I was able to discover the dates and details of the dangerous missions Dad flew. Through Des, I contacted Kevin Bending who was in the process of writing “Achieve Your Aim The history of 97 (Straits Settlements) Squadron in the Second World War,” in which Jack features. Kevin later took over as Webmaster. My brother also searched the archives at Kew and slowly we began to piece together Dad’s logbook.

In 2010, I received an email from Dick Decuypere, a Belgian author, who was writing about the bombardments in Courtrai (Kortrijk) and Wevelgem in 1944. He had contacted Kevin Bending to search for any surviving airmen of 97 Squadron who had taken part in the 20/21 July raid and relatives who might be able to add personal photos and stories. I sent him two photos of Jack which were included in his book De Luchtaanvallen Op Kortrijk en Wevelgem. Later that year I received an invitation to attend the book launch in Courtrai, Belgium and to a memorial service the day after, which I accepted. My husband encouraged me to attend.

It was snowing when I arrived alone in Courtrai in November. I’d no idea what Dirk looked like or even if I’d turned up at the right place, dependent on the taxi driver and the address on my invitation. The moment I opened the building door and saw the large seated audience I knew it was a big event. More people stood in front of a stage set with a siren and backdrop of wartime pictures. I must have looked lost as someone asked me a question in Flemish. Immediately I replied in English a man hurried over. It was Dirk. After greetings, he led me to an empty seat in the front row and introduced me to Pol Descamps, the Belgian man beside me. The siren wailed, opening the proceedings. The sound took me right back to the war as a child. Dirk spoke in Flemish and Pol rose to his feet to receive the first copy of Dirk’s book. I learned Pol had been in the cellar with his mother the night of the bombing on 21 July. He was sitting on her lap when an explosion threw him out of her arms. She died and he survived. He had lost his mother the same night as I lost my father but still he thanked me for Dad’s sacrifice, despite the bombardment of Courtrai. I was astounded by his sincerity. He signed the flyleaf of my book.

Then it was my turn to go up to the lectern and receive my copy. A photo of my father, mother and me flashed onto the stage screen. Dirk spoke in English first and then Flemish, again thanking me for my father’s sacrifice. Totally overcome, my tears welled up for Dad, my hero; for my late Mum who had loved him; my brother and me who had grown up without him.

Others went up to collect a book. A family from Australia first, then Percy Cannings, who had been a rear gunner in 97 Squadron and had taken part in the raid. He’d not met Jack. Other veterans from different squadrons were honoured. After the book launch we visited the rooms at the rear of the hall where there was a display of memorabilia from other crash sites: parachutes, parts of aircraft engines, items of clothing and personal effects of airmen discovered by a team of researchers. On the walls, posters hung telling stories of air crew who had taken part in the raid and there was one of Dad.

The following day my sons, Gavin and Ross, arrived from the UK to take part in the memorial service. We drove to Bissegem, an area of Courtrai, to the site of a Lancaster bomber from No 9 Squadron that had crashed on 21 July 1944. The memorial stone was carved from granite in the shape of a Lancaster bomber tail plane citing the names of the dead crew. Percy was asked to read the first verses of “For the Fallen” by Robert Binyon and I the last. The RAF Hymn – Per Ardua Ad Astra - filled the air. Words were spoken, flowers laid upon the memorial. I placed three poppies, one from each of my sons and me.

Then it was time to read those famous words “They shall not grow old…”

Jackie and her sons, Gavin and Ross, at the memorial in Bissegem

In 2014, my brother Ross designed a prototype memorial for those squadrons that had flown from Bourn airfield during WW2. He also arranged for the two remaining airworthy Lancasters, one from the Canadian Warplane Heritage who came over for the 2014 UK tour and the other from the Battle of Britain Memorial Flight, to fly past Bourn airfield on Sunday 24 August at 3pm. I was there with Ross, his family, and veterans who had come to watch this historic event.

The sound of the Avro engines came first and then the iconic shape of the Lancasters. With a roar they were overhead and I saw the bubble beneath the cockpit where my father had lain exposed in preparation for bombing, increasing the admiration I had for him and his courage. At this event I met Eric Rimmington, my father’s friend from the Benton crew. ‘I can’t believe I’m talking to Jack’s daughter,’ he said, both of us in tears.

L-R Jackie, Eric Rimmington and his wife, Renee in 2014 (Credit: RAF Pathfinders Archive)

As a young woman I followed my brother into the army. Like Ross and my father, I wanted to serve my country. I am indebted to the RAF Benevolent Fund who paid for my education as a result of my father’s sacrifice. And I am grateful to be able to share Jack’s story and discover his name on column 210 at the British Normandy Memorial listed with his valiant comrades who died with him on 21 July 1944.

FALLEN HEROES

JACK SKINGLEY

Royal Air Force • FLIGHT LIEUTENANT

Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve

97 (Straits Settlements) Squadron, Royal Air ForceDIED | 21 July 1944

AGE | 28

SERVICE NO. | 134721

FALLEN HEROES

JACK SKINGLEY

Royal Air Force • FLIGHT LIEUTENANT

Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve

97 (Straits Settlements) Squadron, Royal Air ForceDIED | 21 July 1944

AGE | 28

SERVICE NO. | 134721