John Edis Spence's Normandy experience

This story and photos are shared by the Trust courtesy of Annie Ross, née Spence, based on the autobiography of her father, Canon John Edis Spence and the Tank Museum, Bovington

The weeks before D-Day were days of great tension and excitement, with a certain degree of apprehension as to what fate would befall us when we crossed the Channel. The days were spent firstly waterproofing the tanks, so that they could be launched into fairly deep water successfully from the Landing Ships Tank (LST).

Like all units of British Second Army in those last weeks the regiment was more or less sealed off from the outside world to maintain security and prevent any leaks about the date of the invasion. Apart from work, we were restricted to football matches among the squadrons and film shows at night. Our one visit to the world at large was for a conference of all officers held by the Divisional Commander at a cinema in a local town.

On all the roads were masses of men and materials all moving in the direction of the embarkation ports. The three regiments of 22nd Armoured Brigade sailed from Felixstowe in US Landing Craft Tanks, and the soft vehicles of the Brigade sailed from Tilbury. No-one who sailed down the Channel will ever forget the sight of it. The passage was very cramped, the weather was unpleasant with frequent squalls, and the tank crews were feeling very seasick. Everyone was wondering whether with these conditions the operation might be postponed.

As we entered the Channel more and more ships were gathering all moving towards the French coast. There was this mighty airborne armada overhead and with such a show of strength we were encouraged with the thought that this invasion could not fail. After lying well out to sea for some time we were eventually disembarked on the beaches. The scene there was one of intense activity, with Royal Navy Beachmasters trying to maintain a semblance of order.

There was a constant stream of landing craft and DUKWs (amphibious vehicles) bringing ashore men, stores, fuel and ammunition, and as soon as these were unloaded, they were taking back wounded and prisoners of war back to England. Above the beaches floated captive barrage balloons to deter low flying enemy aircraft, as a steady stream of allied fighters flew inland to attack enemy targets, and heavy naval ships laying off the shore fired continual broadsides against enemy targets in front of our own troops.

It was in those first few weeks in Normandy in the bocage country that two of my crew were wounded, and they both happened to be my drivers. The first occasion when this happened was at night near Tilly-sur-Seulles. We were often being subjected to shelling and the occasional night air raid by a sneaking German bomber. To protect against this at night we dug a trench near the tank so we could jump in for protection.

This night, when the first shell landed, we took cover, but my driver under the tarpaulin beside the tank decided he must first put on his trousers. During the time he was struggling to get his battle dress trousers on, a shell landed close, and a fragment hit his legs. It was my first experience to put a shell dressing on his wounds with only the aid of a torch to see what I was doing. After it was successfully applied, and we had given him a shot of morphia we carried him over to the doctor’s half-track.

The second driver I lost through injury was some days later when the regiment was on the march, and we were travelling on a road that had been used by hundreds of vehicles, when it was my tank that exploded a mine. Again, from the explosion the driver was wounded in the legs, and we had to get him out of the driver’s compartment before we could attend to his wounds. The tank was out of action since one of the tracks was blown off, but fortunately the remainder of the crew including myself were unharmed apart from a certain amount of deafness for a few days. As in the previous occasion we soon moved him to the doctor and speedily he was on his way back to the casualty clearing station en route to England.

The first battle in which the brigade was involved was close to Villers Bocage, where our sister regiment, the 4th County of London Yeomanry, which was in the lead suffered serious casualties and lost most of their regimental headquarters and a Squadron through the unexpected arrival of a Panzer division in the neighbourhood.

One of the great joys and delights of active service in tanks was the close communal life and fellowship that was shared by the crew. Officers and men lived and fought and frequently died together in the closest proximity.

They spent each long day side by side in the turret, making a brew of tea whenever possible, and kept going for long periods at a time with a packet of hard biscuits and a tin of Players cigarettes on the shelf just inside the cupola. They ate together from the compo rations carried on the tank, doing their cooking with a petrol can filled with some earth and some petrol poured over it. They slept alongside each other under a tarpaulin draped over the side of the tank. the result was a great bond of friendship between all members of the crew.

They knew all the virtues and failings of their companions, and from this real sense of brotherhood there arose an amazing spirit of unselfishness. They were prepared to share everything with each other, to sacrifice for each other, even if it meant the sacrifice of their own lives. When a member of the crew was wounded or killed, there was a great sense of sadness in that little body of men. The vacuum left was felt very strongly, though the replacement member had to be warmly welcomed into the circle straightaway.

I lost two of my tanks and several members of the crew. Apart from the ones already described, I also had my wireless operator wounded in a night raid by the Luftwaffe. He unfortunately had a fragment of shrapnel in his testicles, not an easy part of the anatomy to dress. To make matters worse, it was during that raid that our doctor was killed in his half-track. I had a letter a few weeks later from the operator proudly telling me that his marital prospects had not been affected by his wounds.

Everyone who fought in Normandy, still to this day, has vivid memories of the sights, sounds and smells that they had witnessed there. This was especially true of what they had experienced in the bocage country from Bayeux to Caen and from Falaise on to the Seine.

There were the sights of the destruction of the farmhouses and villages which we had come to liberate, a tremendous amount of destruction brought about through the hard battles of the German resistance. There was the terrible smell of dead, bloated cattle lying in the fields, and often the smell of human dead. There was the strange odour that seemed to come from all captured German equipment and vehicles and that pervaded the uniforms of the prisoners. Then there were the sounds, most of them very frightening; the high staccato noise of the Spandau machine gun; the screaming whine of the ‘Moaning Minnies’, the multi- barrel German Nebelwerfer mortar, and the thunderous crash of the falling 102mm large German shells.

One of the hardest actions in the campaign was the battle around the city of Caen. It was during those following days of hard slog and constant shelling that my driver, Trooper Melvyn Stone, was killed. You can read more about his Story here.

From the Church Times, 12 October 2012. Part of an obituary for the Reverend Canon John Edis Spence written by the Reverend Gorran Chapman:

The loss of Trooper Melvyn Stone strengthened in John the call to a vocation felt even before university; and it also inspired his lifelong enthusiasm as a member of the Royal Tank Regiment Association, and great affection for the spirit of comradeship among his tank crews.

He was involved in combat from Normandy to the end of the war on the German/Danish border north of Hamburg. He encountered the survivors of liberated concentration camps, which confirmed his belief that the war had been just.

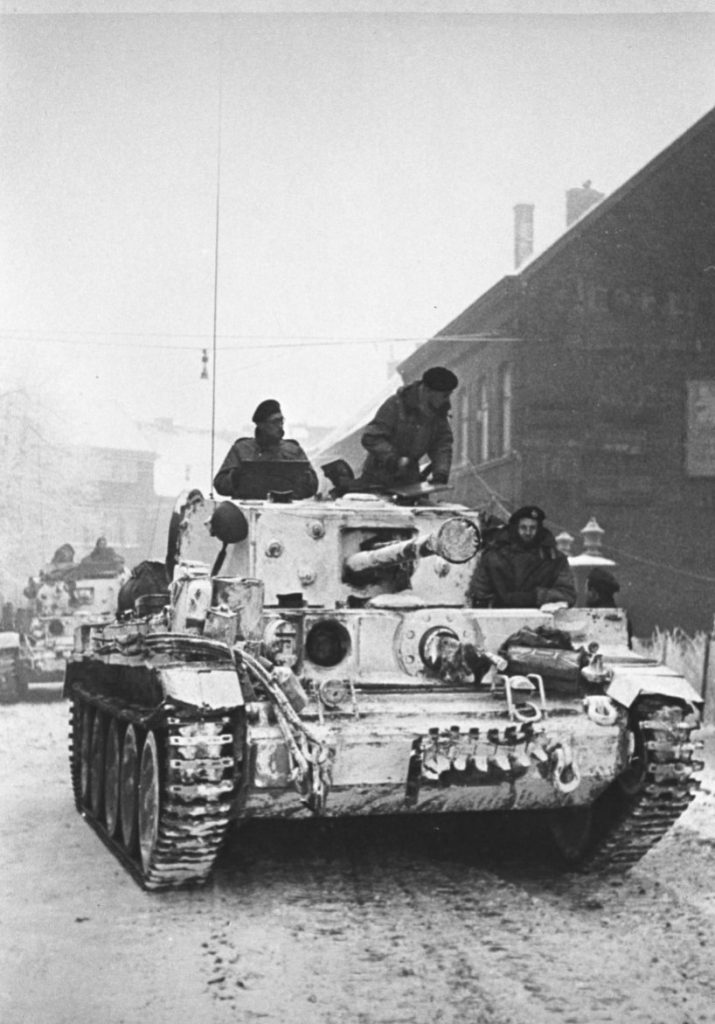

John Spence, standing up on the right, with his tank crew when in the Netherlands © The Tank Museum